The subject of forgiveness has been much on my mind over the past few days. Specifically: when a person is deeply wronged by somebody they should be able to trust, is there any way back?

To make my point, I’m going to use some examples from the world of celebrity– but the principles apply to us all.

Director Roman Polanski was found guilty of the statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl in 1977, but fled to Europe before he could be sentenced. Now, a court in Poland says it will not extradite him to the United States, where the offence occurred.

London-based Australian musician and television host Rolf Harris, whose funny records and exaggerated persona I loved as a child, was jailed at the age of 84 last year for sexual offences against four female victims stretching back 40 years. The court heard, among other things, that Harris had had a long-running relationship with a teen-aged friend of his daughter, and that it had ruined her life.

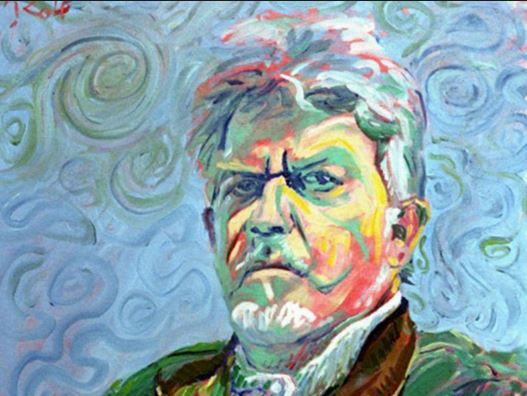

Woody Allen, one of my favourite filmmakers, stands accused or molesting his adoptive daughter Dylan Farrow. But police, the Connecticut state attorney and child-abuse experts decided there was insufficient evidence and that the girl appeared to have been “coached” in giving evidence. That was in 1993, yet there are some people today swear that Allen is guilty.

Three well-known cases — and all of them different. In the Harris case, the court found him guilty and he is in jail; in the Allen case, due process was followed and charges were not laid, yet allegations remain. Polanski, meanwhile, seems to have escaped justice altogether.

In any case that is serious enough to go to court, the legal system plays its role in determining innocence or guilt and, in the latter case, setting an appropriate punishment. Sometimes the police, prosecutors, judges and juries get it wrong; usually they get it right.

Beyond that, the rest of us just have opinions. We can boycott films or rant on our blogs and social-media sites, but that won’t get us any closer to the truth. And, at the end of the day, when it comes to strangers, it’s really none of our business.

But what about an incident of actual harm or betrayal that involves somebody we know?

Sometimes the circumstances are opaque — nobody knows the truth except those who were there, and they provide different, self-serving versions of events.

When there are two “truths” to choose from, how do we know we have chosen the correct one? Do we have to take sides, or should we sit on the fence? But by doing nothing, do we embolden the perpetrator and betray the victim?

In any genuine case of wrongdoing by one person against another, we can, and should, offer our support. But only the victim can decide whether they will offer forgiveness.